Article

5 min read

UK workers are avoiding the £100,000 tax trap, and parents are leading the way

Author

Lauren Thomas

Published

November 20, 2025

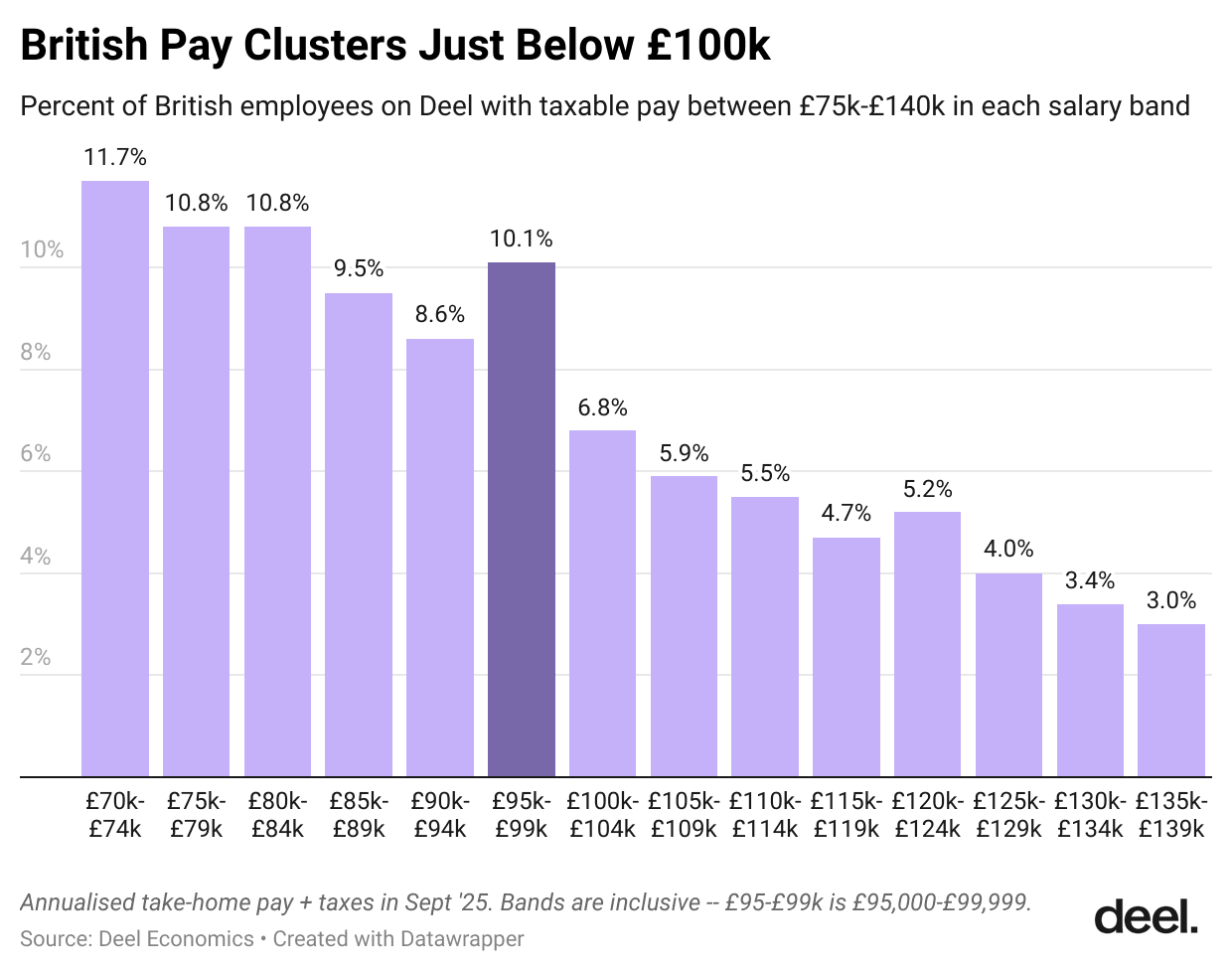

New payroll data reveals employees clustering just below the £100,000 threshold to avoid punishing marginal tax rates and childcare benefit losses.

Economics teaches us that people respond to marginal incentives. But is that actually the case in the real world? Deel’s data delivers a resounding ‘yes’.

Analysis includes the October 2024-September 2025 paychecks of thousands of UK employees on our platform1. Taxable pay = net pay + taxes (equivalent to gross pay - pre-tax salary sacrifice contributions).

The taxable pay of UK employees on Deel clusters sharply just below £100,000 —evidence that the high marginal tax rates are incentivizing workers to earn less than that. The loss of funded childcare hours at £100,000 appears to have an even stronger effect. Parents of young children, proxied by the postcode in which they live, are more likely to bunch just below the £100,000 threshold than non-parents

These patterns have implications for the Autumn Budget coming out next week. Higher marginal tax rates, even if they’re not specifically targeting the £100,000-plus bracket, will likely further push employees to earn under £100,000 in taxable pay.

The £100,000 cliff

When an employee hits £100,000 in gross pay (base, bonus, commission, equity, and benefits in kind), they face a 62% marginal tax rate until they hit £125,000. For every extra £2 earned between £100,000 and£125,000, they lose £1 in tax-free personal allowance. That means the 40% marginal tax rate jumps by 1.5x, with an additional 2 percentage points in National Insurance contributions on top.

For parents of young children, it’s even worse. At £100,000, they immediately lose access to 30 hours of government-funded childcare per week.

There’s a strong incentive to avoid crossing that threshold, especially for those earning only slightly above it. There are two ways to avoid that cliff: earn less money (taking fewer shifts, going down to a four-day work week) or shovel more money into your salary sacrifice schemes. Taxes are only levied after that salary sacrifice money is taken out of your paycheck. Those schemes are mostly for retirement savings (most British employees can add up to £60,000 each year in pre-tax deductions to their retirement pot), but they also include Cycle to Work, electric car leases, and more.

Previous analysis of income data of taxation data from the Centre for Analysis of Taxation has shown a big spike at £100,000. We should see the same thing in Deel data, which serves thousands of British employees. But do we?

Indeed, we do! Looking at an annualized version of September 2025 paychecks, we can see a sharp spike in employees earning just under £100,000, a marked difference from the rest of the nearby pay distribution. Full-year taxable pay data shows the same result.

Deel’s detailed payslip data means we can dive much deeper into the data than anyone has publicly before.

Parents bunch more than non-parents

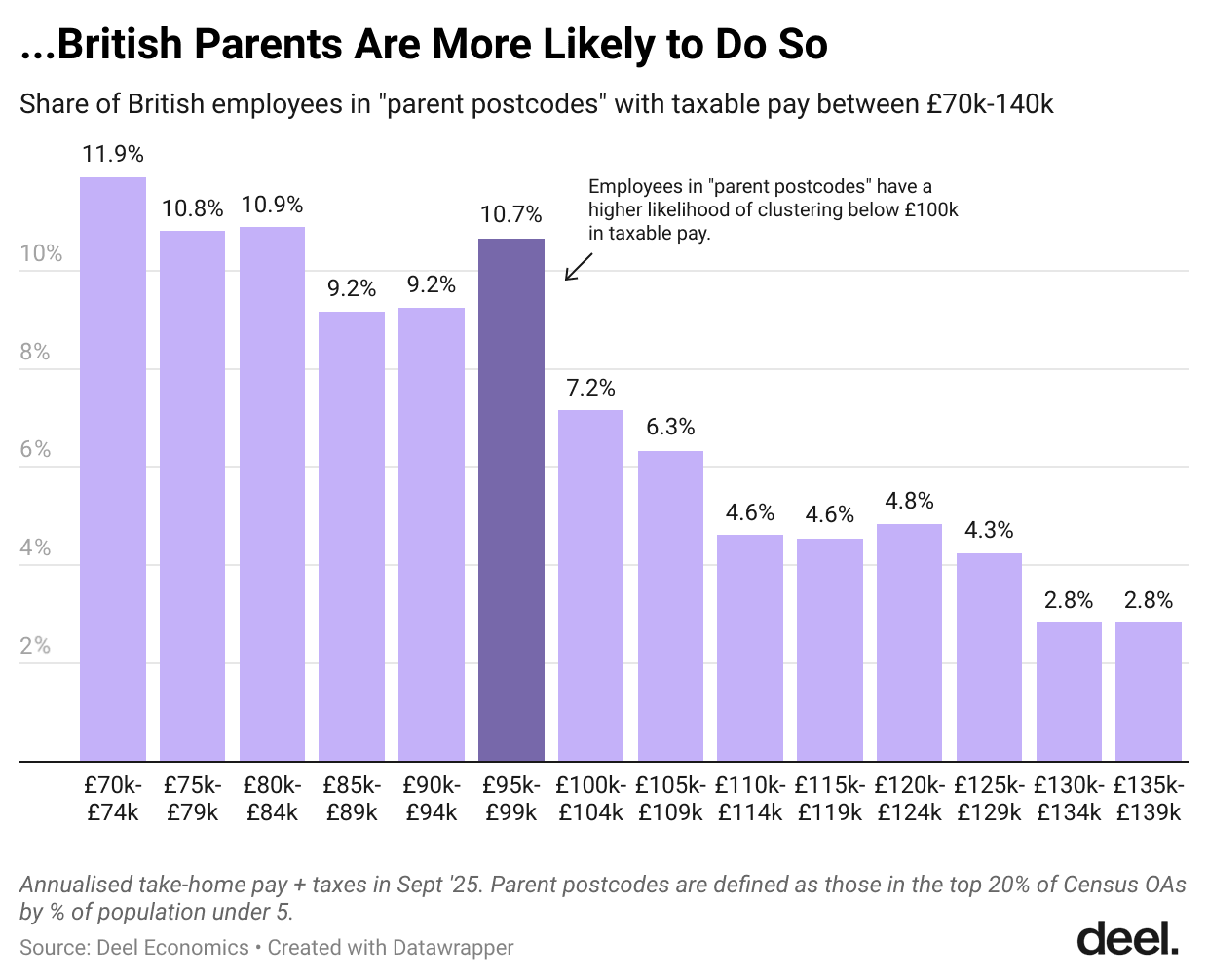

High-income parents face a dual penalty: the 62% marginal rate plus the loss of childcare funding. That should mean that parents care more about the £100,000 tax trap than non-parents do. What does our data show?

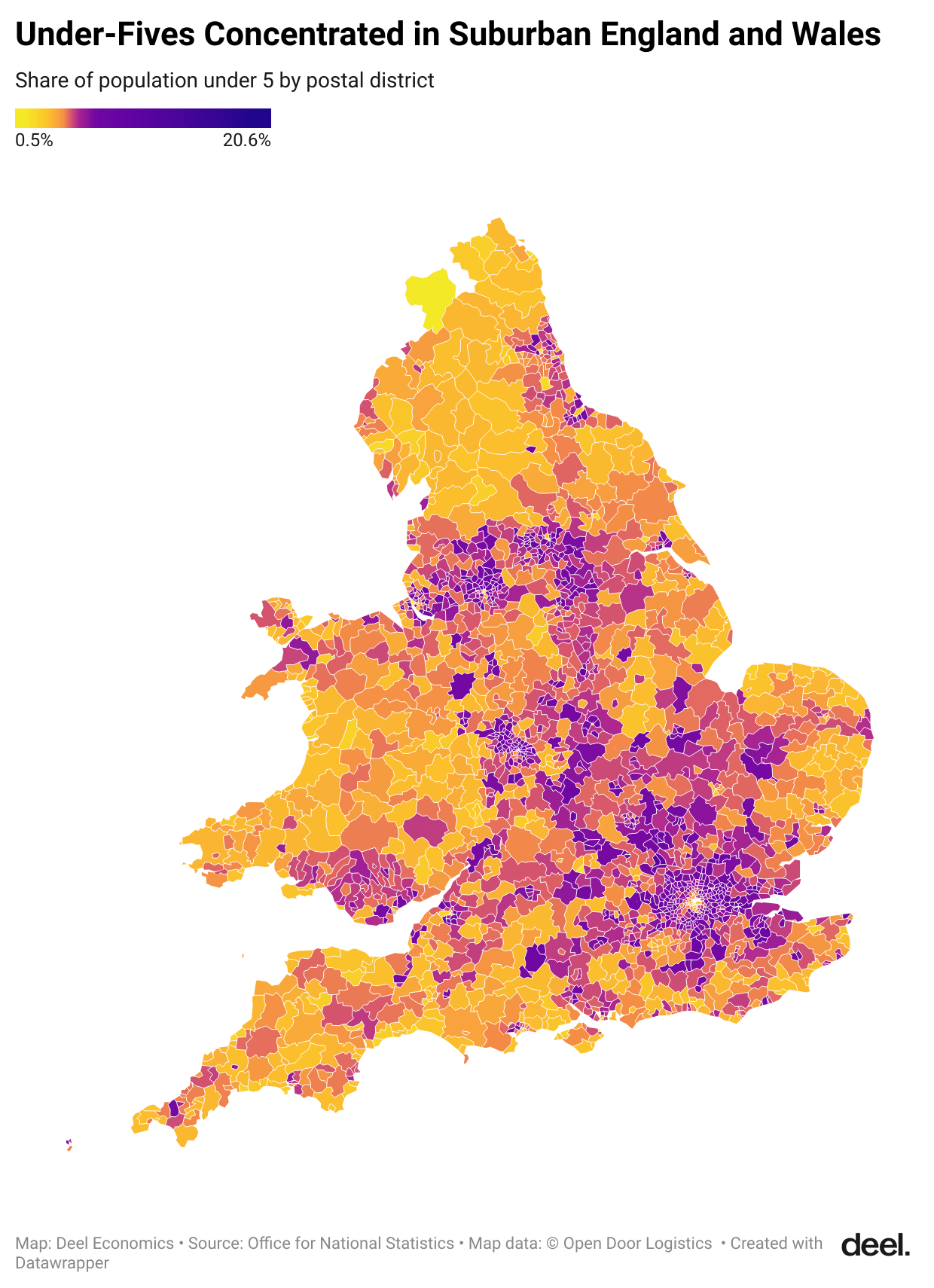

We can’t directly observe whether employees on Deel’s platform have children, but we do know the postcode in which they live. The UK government provides the age distribution data at the census “output area” level—small geographic units, sometimes a single street, made up of several postcodes. This allows us to estimate with reasonable certainty whether or not someone is likely to have children under five from the postcode where they live. Unsurprisingly, those postcodes tend to converge in suburban areas.

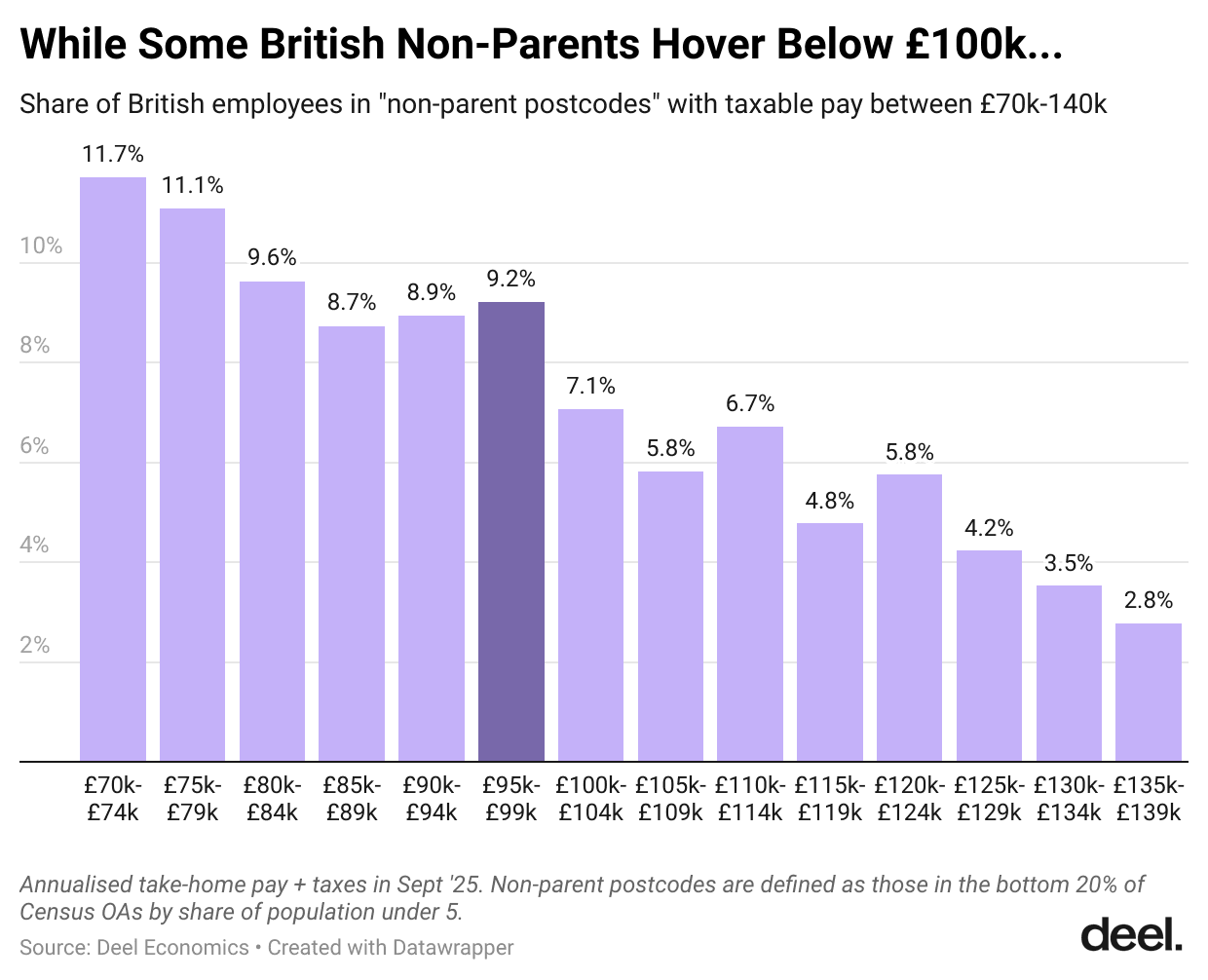

I compared the taxable pay of our employees living in “parent” and “non-parent” postcodes. “Parent” postcodes were the top 20% of employee postcodes by concentration of under-fives.“Non-parent” postcodes were the bottom 20% – that is, they have the lowest share of under-fives.

The charts above show that while the £100,000 tax trap impacts both groups, parents are more likely to cluster just below the threshold.

What this means for the Autumn Budget

These results have big implications for the Autumn Budget coming out next week. Media reports suggest the Chancellor is considering raising marginal tax rates on those earning above £50,000. While this might seem irrelevant, a two percentage point rise in tax rates above £50,000 would mean marginal tax rates at £100,000 rise by 3 percentage points—from 62% to 65%. Our data suggests that this would likely further push employees to keep their taxable pay under £100,000—a result that is hopefully being factored into any potential tax take modelling.

This is just a taste of what’s to come here. If you have ideas for what we should dig into next—salary transparency, job title inflation, global pay trends—drop me a note. I’d love to hear them.

Footnotes

-

Some analyses were September ‘25 only, whereas others covered the time period between October 1, 2024 to September 30, 2025. ↩

Lauren Thomas is Deel's founding Economist, where she’s helping to bring Deel’s mission of breaking down geographic barriers to opportunity to life through data — a mission that resonates personally, as she's worked and studied in six cities across three countries!

Before joining Deel, Lauren worked in economic research and data storytelling at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Glassdoor, and Stripe. She has degrees in economics and data science from Oxford, Université Lumière Lyon 2, and Northwestern University.

Outside of work, she enjoys reading, playing volleyball, climbing, sewing her own clothes, and using Oxford commas. She does not enjoy long flights but takes a lot of them anyway!